Enhanced participation and local action: Decentralising climate finance

14 November 2019, Alexandra Milano, Category: All insights, News, Tags: Climate justice, Concept note, gcf, GGGI, Indonesia, NDAs, Proposal writing, Training

In 2015/2016, global climate finance flows were estimated at USD 463 billion, with USD 214 billion coming from public funding [1]. It’s unknown how much of that money went to fund local activities, but the number seems to be minimal, as between 2003 and 2016, less than 10% of climate finance (USD 1.5 billion) went to local projects. Why is this? The answer is complicated.

What’s less complicated is the role of climate justice in disbursing this money. A number of climate justice principles are relevant to climate finance, none more so that participation. Participation is enabled by decentralising climate finance; that is, making climate finance more accessible to local actors on the ground so that they can identify their priorities, manage funds and implement successful projects. At the same time local action is an effective way to maximise participation—participation and local action are intertwined.

Participation: A key principle of climate justice

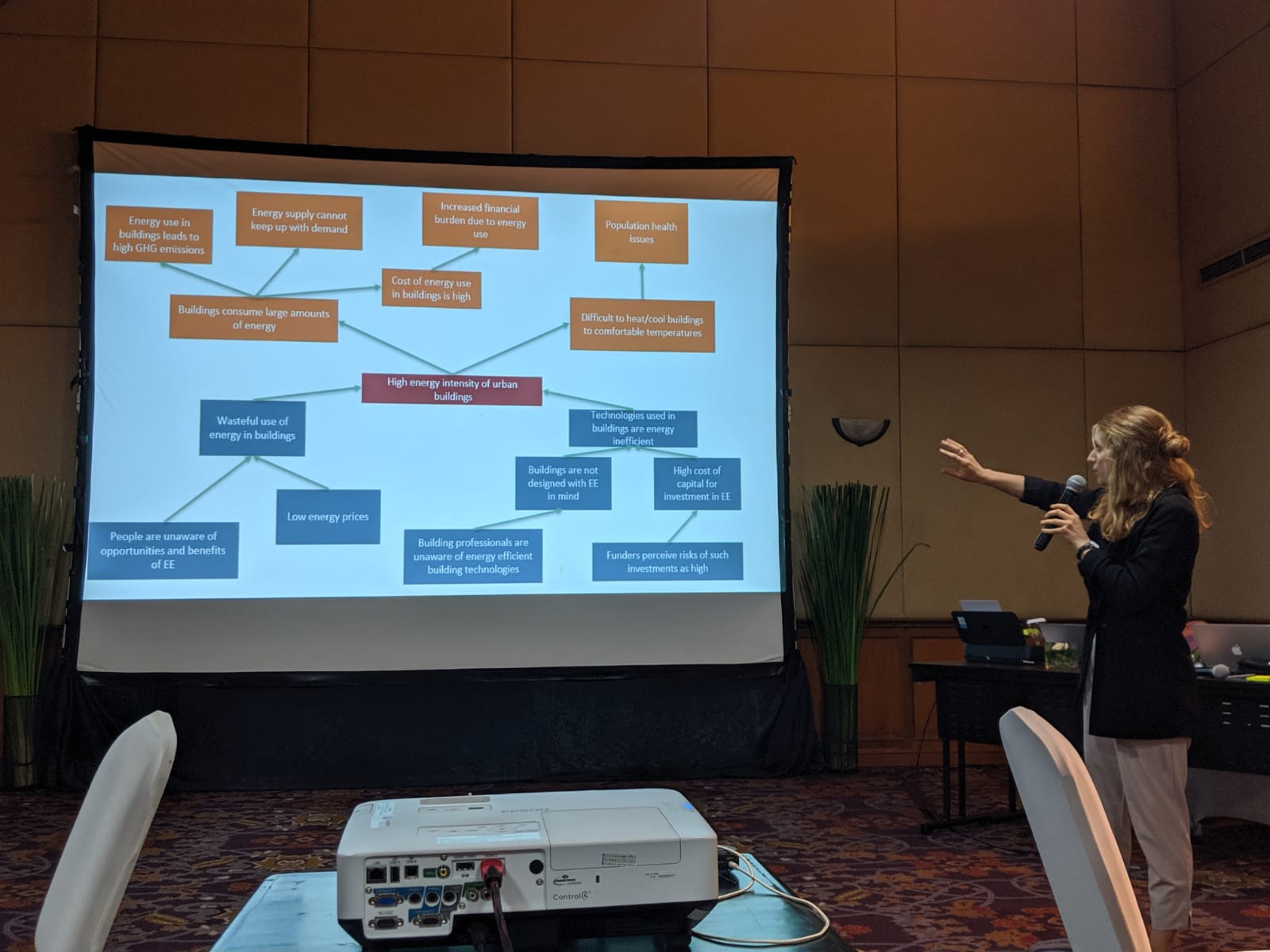

Participants developing their own Problem and Objectives trees in a group exercise

Participation is a core tenet of climate justice. According to the Mary Robinson Foundation, “The opportunity to participate in decision-making processes which are fair, accountable, open and corruption-free is essential to the growth of a culture of climate justice.” In other words, everyone, especially the most vulnerable, must be able to meaningfully participate in decisions related to climate change. This includes issues like policy development but also investment priorities: the areas where a country, donor or other actor decides to invest should be guided by the needs of the most vulnerable.

Participation can take a number of forms. In project design, this typically means stakeholder consultations. If we’re designing an adaptation project on climate resilient agriculture, our methods may include interviews and focus group discussions with smallholder farmers to establish current agricultural practices and understand their concerns. We may go on transect walks or undertake a participatory mapping exercise to identify priority areas for intervention. But if we take a more macro view of our project, important questions about participation arise:

- Who decided this type of project was needed?

- Who designed the project?

- If the project is funded, who will control the money?

Country ownership vs. local ownership

In the majority of cases, the answer will be an international organisation. Ultimately, decision-making power lies exclusively with the international organisation. National level actors will be consulted and ultimately endorse the project to signal country ownership. The project will be required to demonstrate alignment with national policies, plans and priorities. National stakeholders will also be involved in the management of funds and implementation of the project.

Country ownership is not indicative of local ownership. Major climate funds encourage local stakeholder consultation as part of country ownership, though the impact of these consultations is unclear. Similarly, the effectiveness of such consultations is limited when local stakeholders have little decision-making power. For example, the smallholder farmers consulted in our example project were asked questions that were framed in support of a project the international organisation already intended to implement. They would have been consulted, yes, but these consultations would not amount to a meaningful form of participation. The questions that were asked assumed that the project was in line with their needs—they weren’t given an opportunity to identify their own priorities. How do we prevent situations like this from happening?

Decentralising climate finance

E Co. consultant Alex Milano leading a session on Problem and Objectives analysis

It’s here that climate justice has a key role to play in the development of climate finance projects, especially in adaptation. To catalyse the meaningful participation of local actors, climate finance must devolve beyond international and national organisations. Local actors must be able to access (and later, manage) funds to design and implement projects that meet the needs of their communities.

A 2017 working paper prepared by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) identified a number of benefits to this approach, including the fact that participatory decision-making is easier to facilitate at the local level. Local organisations are in closer proximity to the communities they serve, which often enhances accountability and transparent decision-making [2]. Had our earlier example project been designed and implemented by a local organisation, it is likely that the smallholder farmers would have had a more meaningful role in the project design process and, hence, stood to gain more from it.

Currently, it is unclear exactly how much climate or development finance flows to local actors [3]. As I mentioned earlier, it’s estimated that between 2003 and 2016, less than 10% (USD 1.5 billion) of finance from international, regional and national climate funds supported local activities [4]. Considered in the larger context of total annual funding, this figure indicates a clear shortfall of funding for local climate action.

What can be done to open up climate finance for local activities?

E Co. CEO Grant-Ballard Tremeer in open discussion with participants during the workshop

There are a number of obstacles preventing local actors from accessing climate finance. A critical issue is the arduous nature of submission process for major climate funds. This is something we often see at E Co; the process to design and submit bankable projects is long, complicated and resource intensive. It can be a struggle even for large international organisations and prohibitive for smaller, local organisations. So, how do we change this?

E Co. is working at the local level to help build capacity in project design and preparation. Last month, my colleague Grant and I travelled to Jakarta, Indonesia to deliver a participatory training to local stakeholders on the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Supported by the Indonesian NDA and GGGI Indonesia, the training spanned two and a half days and covered a host of topics. Attendees included local civil society organisations, private sector actors, and local government. Participants had been pre-selected by the NDA and GGGI following a call to submit project concept notes.

The first half day session was hosted by the NDA and provided an introduction to the GCF and several other topics, including country ownership, the Simplified Approval Process, the Private Sector Facility and others. E Co. covered the remaining two days and delivered a number of sessions. These included:

- GCF investment criteria

- Project identification

- Stakeholder analysis

- Problem and objective tree analysis

- Theory of change

- Barrier analysis

- Climate rationale

- Results frameworks

- The project logic

- Project risks, assumptions and indicators

- Institutional arrangements

- Annexes, studies and gender requirements

- Project finance and budget preparation

- Private sector engagement

- Co-financing

This is the second training E Co. has done in Indonesia. We have also done similar trainings in other countries, including Ethiopia, Guatemala, Morocco, Mozambique, Uganda, Vietnam and Zimbabwe. From 2014-2019, together with the University of Twente, we ran an international course on project development for the GCF. Our hope is that trainings like these will not only increase the number and quality of climate finance proposals, but that more of these projects will be locally owned and driven.

Is capacity building enough?

More participatory-style group exercises during the workshop

Capacity building trainings like these will help make climate finance more accessible to local actors. However, training alone is not enough to decentralise climate finance. There’s still plenty of work to be done. Climate funds must relax some of their stringent application processes and requirements for co-finance. Additionally, an emphasis on large-scale results means that smaller energy access projects, for example, may be overlooked in favour of projects with higher carbon reductions [5]. The IIED paper notes that there’s also a need to diverge from business as usual. Multilateral development banks “are less comfortable implementing small-scale funding” but in some cases it is possible to channel funds through local intermediaries such as banks or even CSOs [6]. Similarly, climate funds have demonstrated risk aversion and a preference for the use of concessional loans. This has led to a partiality for large scale mitigation projects [7]. And again, insufficient mechanisms for local participation and ownership of projects result in limited engagement from local communities [8]. These issues must be addressed as a matter of justice so that communities on the front lines of climate change can undertake resilience building activities in line with their own needs and priorities.

Bibliography

[1] Climate Policy Initiative, climatefinancelandscape.org.

[2] Soanes, M, Rai, N, Steele, P, Shakya, C and Macgregor, J (2017) Delivering real change: getting international climate finance to the local level. IIED Working Paper. Available at: http://pubs.iied.org/10178IIED

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, pg. 30.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

Would you like to learn more about our training courses? Click here

This article is a part of Alex Milano’s Climate Justice series. Have you read her first article on ‘The role of climate finance in climate justice’?

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. You can either use your social account, by clicking on the corresponding icons or simply fill in the form below. All comments are moderated.