News: Gender perspectives in the clean energy transition

25 June 2019, Dr. Silvia Emili, Category: All insights, News, Tags: business models, clean energy transition, Communities of Practice, developing countries, gender, gender mainstreaming, global energy transition, inequality, low emission, SDGs, sustainability, sustainable development

Prioritising gender in energy investments

The transition towards a clean and low-emission energy provision requires a significant increase in renewable energy investment compared to current levels. The IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario and Tracking of Clean Energy Progress shows that we are far from being on track. Similarly, Tracking SDG7 found that, despite progress, 2030 targets will not be achieved at the current rate of ambition. Although renewable energy technology costs have been falling progressively, underlying market barriers and a perception of high risk are still major constraints to the development and financing of renewable energy projects in many developing countries.

As part of our GCF Communities of Practice engagement, we have recently started analysing the financial landscape and the enabling environment for renewable energy, energy efficiency and energy access within the clean energy transition of developing countries. While studying existing literature and various databases that outline investment needs, renewable energy potential and developing countries’ mitigation ambitions, I was particularly interested to find gender-specific indicators. How could investors and funds consider gender perspectives when identifying investments priorities? How does an enabling environment that supports gender mainstreaming and women’s empowerment affect GCF investment decisions?

In this article I provide a summary of the barriers and opportunities for gender inclusion in the clean energy transition, and I will briefly discuss entry points and needs for further work.

The nexus between energy access and gender inequalities

Energy poverty affects men and women differently, with gender inequalities playing a significant role on the capacity of women to accumulate resources through value-added economic activities [1]. A clear nexus between energy access and women’s poverty is widely documented, as women’s needs for energy have a practical, productive and strategic impact on their lives and, by extension, the lives of their communities.

These gender inequalities mean that women generally have less access to productivity-enhancing resources, such as labour, collateral, credit facilities, information, and training. These inequalities stem from household-based discrimination and from broader societal and cultural constraints. Across developing countries, women entrepreneurs often own informal businesses. However, attention is usually focused on micro-enterprises and community cooperatives rather than on scaling up women’s entrepreneurship.

The International Energy Agency is tracking clean energy progress and seeking to better understand the role of gender in the clean energy transition. Their focus is on two key areas: the role of gender in the energy sector, and the relationship between gender and energy consumption. While I briefly discuss these two topics in the paragraph below, I argue that tracking progress on gendered policy measures and investments require further attention and doing so could drastically steer and speed up advancements towards 2030 targets.

Missed opportunities

A recent report from IRENA [2] found that globally 32% of women are employed in renewable energy jobs. While these numbers have increased over recent years, structural barriers are still hindering women’s access and participation in the sector. The top entry barriers for women to participate in the renewable energy sector include: perception of gender roles, cultural and social norms and prevailing hiring practices. In particular, the perception of gender roles is directly linked with social and cultural norms which influence women’s career choices as well as lack of access to information.

Women’s representation is particularly low in decision-making positions. According to a 2014 USAID and IUCN report [3] women represent only 6% of ministerial positions responsible for national energy policies and programs in an analysis of 72 countries. Even when women get access to the RE sector, additional barriers hinder their participation in decision-making activities. Men represent at least 75% of board members, making it harder for women to advance in managerial positions. Additionally, there is a lack of flexibility in the workplace for women, which includes dealing with mobility requirements, balancing family commitments and household duties. The lack of mentorship opportunities has been identified as another important factor hindering women’s participation in the renewable energy sector.

Research shows that gender inclusion in the organisation is good for business and female employees, managers and executives can serve untapped female consumer markets. A 2010 McKinsey survey of companies that invest in programs targeting women in emerging and developing markets found that 34% of companies reported increased profits and a further 38% were expecting positive returns [4]. Similarly, a 2016 study by Ernst & Young analysed gender diversity in the boardrooms of the world’s largest energy utilities and found that those with more women on their boards were linked to improved business performance by 14.8% [5].

Understanding gender differences in energy consumption and in how products are used is also a key factor that will shape business models and investments. For developed contexts, the European Institute for Gender Equality [6] found that women are more sustainable consumers than men as they value eco-labelled products and green procurement higher. This study found evidence of gender-specific consumption patterns that affect contributions to GHG emissions, and thus to climate change, and concludes that women have more sustainable consumption habits and are more likely to change their behaviours in adopting greener technologies.

Moving forward in the clean energy transition: recipes for increased access

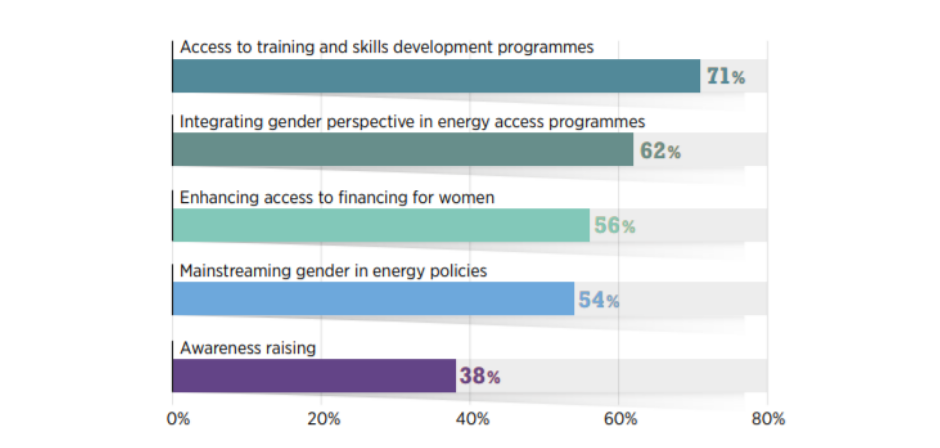

These recent studies provide solid evidence that in order to achieve SDG7 targets and to move forward in the clean energy transition, gender considerations need to play a central role. But how do we move beyond evidence to transform these opportunities into practice? IRENA (2019) highlights opportunities for advancing equality in the energy sector: mainstreaming gender in the energy sector frameworks; tailoring training and skills development; attracting and retaining women as employees; challenging cultural and social norms across different levels (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 – Measures to improve women’s engagement in deploying renewables for energy access. Source: IRENA online gender survey, 2018

Figure 1 – Measures to improve women’s engagement in deploying renewables for energy access. Source: IRENA online gender survey, 2018

These entry points represent important strategies to increase access while simultaneously advancing towards a clean energy system.

In 2018 I investigated best practices in accelerating access to household energy for wPOWER Hub, collecting evidence from organisations championing women’s inclusion and mapping their approaches against existing literature. Findings from this study show that increasing access to women at different levels of the clean energy value chain can be achieved through a comprehensive approach to programming, financing and policy making.

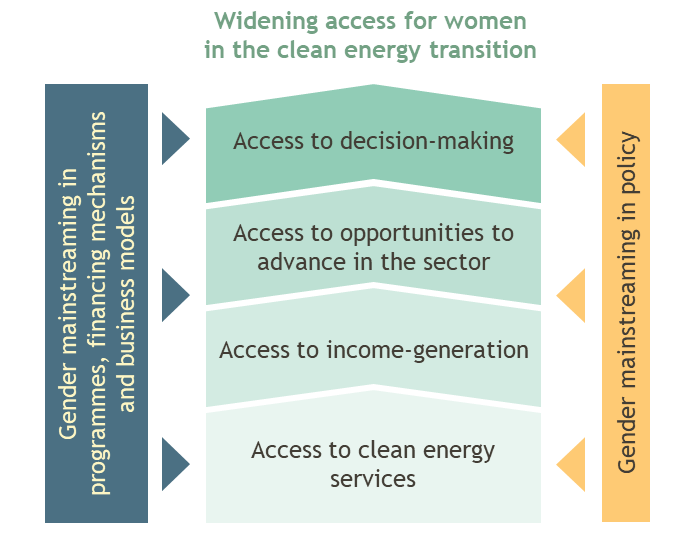

Building on my previous work and on IRENA’s recent findings, I started looking at opportunities for widening access for women at different steps of the clean energy transition (Fig. 2) and how these entry points could be used to inform our work when identifying priority investment areas and financing mechanisms for clean energy.

Figure 2 – Entry points and opportunities for increasing women’s access in the global energy transition

- Access to clean energy services: most of the focus of projects and programmes has been on increasing access to technologies and energy services, where women are simply considered consumers of energy. Increasing access to clean energy services means also increasing their participation in designing solutions, as well as offering solutions that move away from depicting women as passive recipients. Programmes and business models with a gender focus can streamline these considerations in product design, energy consumption patterns, delivery models and services offered as part of energy solutions.

- Access to income-generation: moving up the ladder, this step involves focusing on increasing women’s empowerment through energy, for example involving women in energy supply chains as entrepreneurs and employees or targeting women’s productive uses of energy. Access to information, training and financial services are key to improve women’s access to income generating activities, together with targeted subsidies and investments in energy infrastructure.

- Access to opportunities to advance in the sector: involves increasing access to training, supportive networks and mentorship programmes, flexibility of working conditions and transparent workplace practices among others. For example, within the supply chain, women’s groups can be leveraged for distribution of products as group settings can enhance the ability of women to overcome constraints, both cultural and social. Women within groups may have more confidence, leading to greater opportunities for personal and business growth. Cross-cutting to these steps, gender mainstreaming at the policy level and at the financing/business model level directly shapes interventions to increase career opportunities for women.

- Access to decision-making: the final step involves increasing access for women to occupy decision-making roles at a household level, in energy companies and business organisations, which are predominantly male-dominated, and at the policy level.

Gender mainstreaming in policy and investments: how do we move forward?

These entry points for widening access for women in the clean energy transition are directly dependant on a gender-sensitive enabling environment and on gender mainstreaming in investments and programmes. A IUCN study [8] of renewable energy policies found that only six of 33 examined countries (18%) included gender keywords and considerations. Conversely, national gender equity policies rarely include any targets specific to equity in access to energy services, or employment in the energy sector. Additionally, research found that energy policies that do not explicitly target women often result in inequitable access to energy services between men and women [7]. While some policy programmes, such as the ECOWAS Programme on Gender Mainstreaming in Energy Access have started to adopt this holistic approach, considerable efforts still need to be done.

On the other hand, gender considerations are rarely used to shape high-level investments decisions. How can we apply such considerations when prioritising clean technologies and corresponding financing mechanisms? A first approach involves evaluating business models and promising technologies by assessing their potential according to the women empowerment potential, such as supporting productive uses of energy for women or women-led delivery models.

Another approach involves evaluating the attractiveness of enabling environments by looking at gender mainstreaming at the policy level, and whether a country, for example, is advancing towards equality targets such as equal access to financing, collaterals and opportunities. Investments can be prioritised in countries that show high ambition and concrete actions in achieving those targets.

A third approach involves the participation of women’s organisations and women groups in the decision-making of investments priorities, as well as in the design of climate investments. In this context, climate funds can provide different forms of readiness support for enhancing the inclusion of women, women organisations and groups in readiness support activities, which can range from improving policy frameworks to strengthening capacities of relevant institutions and developing coordination mechanisms.

Conclusions

IRENA estimates that the number of jobs in renewables could increase from 10.3 million in 2017 to nearly 29 million in 2050. This offers great opportunities to mainstream gender aspects in the global energy transition. Increasing access to women, from accessing clean and modern energy services to occupying seats at decision-making tables, will greatly shape how energy is produced and distributed. Greater women’s inclusion will lead to greater success of programmes and investments, technology deployment and adoption, and ultimately will contribute to tackling emissions below the 1.5 °C scenario.

Bibliography

[1] Ramani K.V., and Heijndermans E. (2003). Energy, Poverty, and Gender. A Synthesis. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

[2] IRENA (2019) Renewable energy: a gender perspective.

[3] USAID/IUCN, Women at the Forefront of the Clean Energy Future, 2014, https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/Rep-2014-005.pdf

[4] McKinsey & Company (2010). The Business of Empowering Women

[5] EY Women in power and utilities (P&U) Index

[6] EIGE (2012) Women and the Environment Gender Equality and Climate Change https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-and-climate-change-report

[7] ENERGIA (2019) Gender in the transition to sustainable energy for all: From evidence to inclusive policies

[8] IUCN (2017) Energizing Equality: The importance of integrating gender equality principles in national energy policies and frameworks. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/iucn-egi-energizing-equality-web.pdf

Did you find this article useful? Yes 🙂 No 🙁

Have you read Silvia’s last article on ‘The sustainability problem of solar power: end-of-life strategies for the off-grid sector’?

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. You can either use your social account, by clicking on the corresponding icons or simply fill in the form below. All comments are moderated.